Notes of IIIS Operation Systems and Distributed Systems course, Autumn 2022, taught by Prof. Wei Xu.

- Real-world coding

-

performance, scalability, fault tolerance, cooperate

-

How to evaluate a system?

- How to solve the above challenges? Engineering Principles ot system design.

- Learn how existing systems work?

Challenges for modern system design:

-

Running on a Range of Devices

- No more Moore’s Law

- Software Complexity

-

Less qualified programmers

- Internet Scale: $>1$ billion Hosts

1 OS Overview

Users are the biggest enemy to any system.

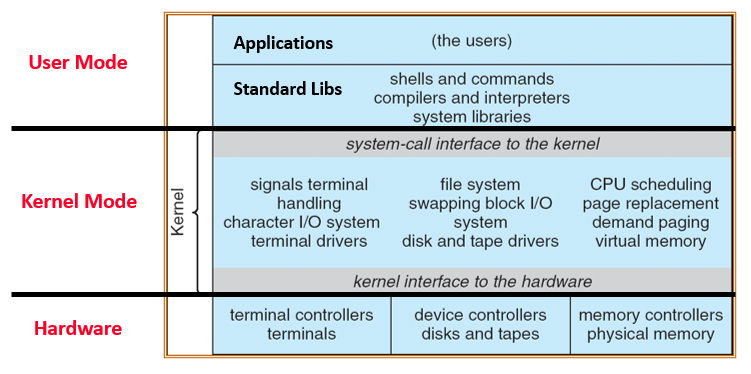

What’s an OS, really? “The one program running at all times on the computer” is the kernel

- Everything else is either a system program (ships with the OS) or an application program

Abstraction, protection

2 Synchronization(1)

Concepts

Thread: single unique execution context

- A thread is executing on a processor (core) when it’s resident; is suspended (not executing) when its state is not loaded (resident) into the processor (stored in memory).

Address Space: The set of accessible addresses (Valid domain as interface)

- Protection mechanism: each process’s memory is protected.

- Address space translation (Virtual address)

Process: Execution environment with Restricted Rights

- With protected address space and 1 or more threads

- OS protected from user’s processes.

Dual Mode: hardware supports at least two modes: kernel and user (a bit of state)

- certain operations / actions only permitted in system / kernel modes;

- User to Kernel transition sets system mode AND saves user PC;

- Kernel to User transition clears system mode AND restores appropriate user PC;

Types of mode transfer: syscall, interrupt, trap or exception

Process from user level

Creating processes: fork(), copy current process and return pid >= 0

Wait for a process to finish: wait()

Change the program being run by the current process: exec()

Set handlers for signals sigaction()

Cooperating threads

Advantage: share resourses, speed up, modularity

Thread pools, representing the maximum level of multiprogramming

Concurrency Problems: Shared data, sharing granularity

- Atomic Operation: an operation that always runs to completion or not at all.

- Indivisible

- Fundamental building block

- Synchronization: using atomic operations to ensure cooperation between threads

- Critical Section: piece of code that only one thread can execute at once

- Mutual Exclusion: ensuring that only one thread executes critical section

- Lock: prevents someone from doing something

Ideas of Synchronization

- lock everything

- busy waiting

- Atomic operations: section of code between

Lock.Acquire()andLock.Release()is a Critical Section

Semaphores

integer, a kind of generalized locks

P(): proberen (to test). An atomic operation that waits for semaphore to become positive, then decrements it by 1.- Think of this as the wait() operation

V(): verhogen (to increment). An atomic operation that increments the semaphore by 1, waking up a waiting P, if any- Think of this as the signal() operation

- Producer-consumer with a bounded buffer (FIFO)

3 Synchronization(2)

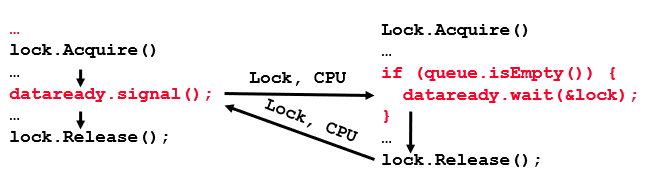

Monitors & Condition Variables

Monitor: a lock and zero or more conditional variables for managing concurrent access to shared data.

Lock: the lock provides mutual exclusion to shared data

- Always acquire before accessing shared data structure, always release after finishing with shared data

- Initially free

Condition Variable: a queue of threads waiting for something inside a critical section

-

Key idea: make it possible to go to sleep inside critical section by atomically releasing lock at time we go to sleep

-

Operations:

-

Wait(&lock): Atomically release lock and go to sleep. Re-acquire lock later before returning. -

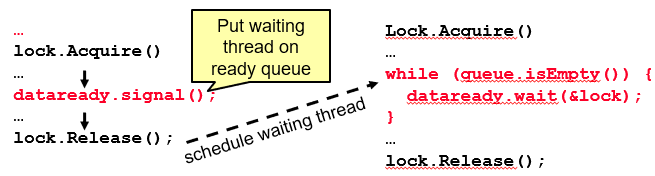

Signal(): Wake up one waiter, if any -

Broadcast(): Wake up all waiters

-

Hoare-style Monitors: Signaler gives up lock and CPU to waiter; waiter runs immediately; waiter gives up lock, processor back to signaler when it exits critical section or if it waits again.

Mesa-style Monitors: Signaler keeps lock and processor; waiter placed on a local ready queue for the monitor; practically, need to check condition again after wait.

Application: Readers & Writers Problem

A shared database, two classes of users:

- readers, who never modify the DB

- writers, who read and modify DB

Exclusive lock & shared lock

Performance Model

Four times of context switching for acquiring and releasing lock.

4.1 MultiThread: Deadlocks

Resources: passive entities needed by threads to do their work

- Preemptable & non-preemptable

- Exclusive access & Sharable

Problems: Starvation & Deadlock

Four Requirements for Deadlock

-

Mutual exclusion: Only one thread at a time can use a resource

-

Hold and wait: Thread holding at least one resource is waiting to acquire additional resources held by other threads

-

No preemption: Resources are released only voluntarily by the thread holding the resource, after thread is finished with it

-

Circular waiting

Solving Deadlock

- All system to enter deadlock and then recover

- Require detection algorithm

- forcibly preempting resources and/or terminating tasks

- Deadlock prevention

- Infinite Resources (Not realistic?)

- No sharing of resources

- Don’t allow waiting

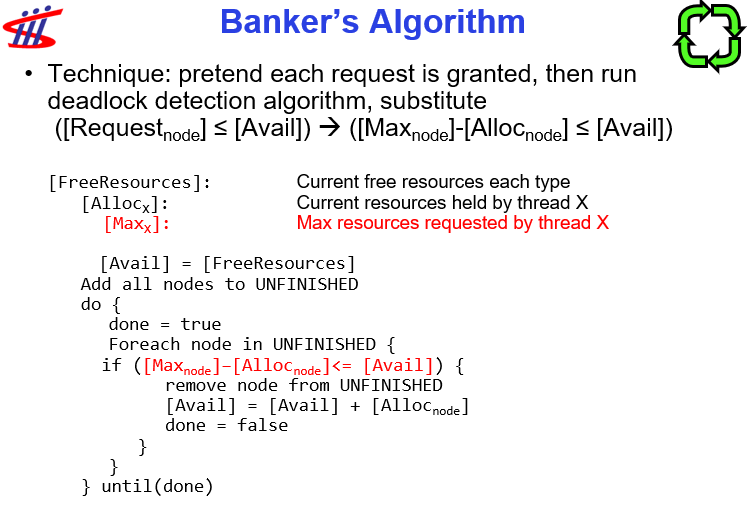

- Banker’s Algorithm

-

Ignore the problem and pretend deadlocks never occurs

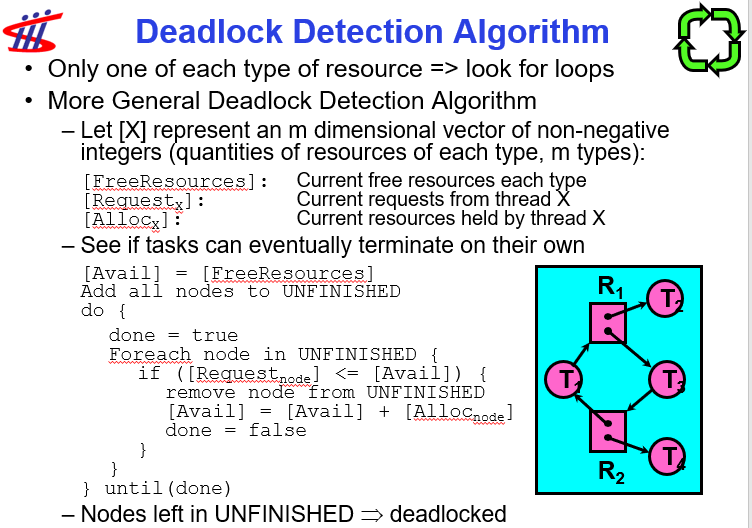

- Resource Allocation Graph

- A set of threads, resources types and instances

Request,Use,Release- Request edge, assignement edge -> directed edges

- Detection Algorithm

[Avail] = [FreeResources]

Add all nodes to UNFINISHED

do {

done = true

Foreach node in UNFINISHED {

if ([Request_node] <= [Avail]) {

remove node from UNFINISHED

[Avail] = [Avail] + [Alloc_node]

done = false

}}} until(done)

Prevention

- Infinite Resources

- No sharing of resources

- Don’t allow waiting

- Pre-request everything that will be needed for the thread to execute.

- Force all threads to request resources in a perticular order.

- Banker’s algorithm: allocate dynamically, keep the system safe.

- Allow the particular thread to proceed if

Avail + Alloc >= Max.

- Allow the particular thread to proceed if

4.2 I/O

Goal: Provide uniform interfaces, despite wide range of different devices

Categories of IO Device Interfaces

- Datatype: Block Devices, Character/Byte Devices, Network Devices

- Timing: Blocking Interface, Non-blocking Interface, Asychronous Interface.

- Kernel-level drivers: for critical devicesUser-level drivers: for non-threatening devices

Example: Memory-mapped Display Controller

DMA (Data Memory Access)

Notifying the OS: Interrupt & Polling

Performance

Response Time = Queue + I/O device service time

-

Metrics: Response Time, Throughput

-

Contributing factors to latency:

-

Software paths (can be loosely modeled by a queue)

-

Hardware controller

-

I/O device service time

-

-

Solutions:

- Make everything faster?

- Decouple systems

- Buffering

4.3 Intro to Queuing Theory

Arrival distribution: Requests arrive following exp distribution $f(x) = \lambda e^{-\lambda x}$

Service time: Mean $m_1$, Variance $\sigma^2$, coefficeint of variance $C=\sigma^2/m_1^2$.

Little’s Law: the average number of tasks in the system (N) is equal to the throughput (B) times the response time (L).

Results:

- Memoryless service distribution (C = 1):

- Called M/M/1 queue: $T_q = T_{ser} \times u/(1 – u)$

- General service distribution (no restrictions), 1 server:

- Called M/G/1 queue: $T_q = T_{ser} \times \frac12(1+C) \times (u/(1 – u))$.

- Disk: $C\approx 1.5$.

5 Networking

Hosts, Connection: multiplexing.

Packet Switching: each packet travels independently to the dst host.

Main Functionalities

- Delivery

- Reliability

- Flow Control

- Congestion Control

Delivery: Multiplexing

Network (Interface) card/Controller: Hardware that physically connects a computer to the network. Each NC is associated with two addresses:

-

MAC/Physical address: 48-bit unique identifier assigned by card vendor

-

IP/Network Address: 32-bit (or 128-bit for IPv6) address assigned by network administrator or dynamically when computer connects to network

Connection: communication channel between two processes. Each endpoint is identified by a port number. Globally, an endpoint is identified by (IP address, port number)

- Port number: 16-bit identifier assigned by app or OS

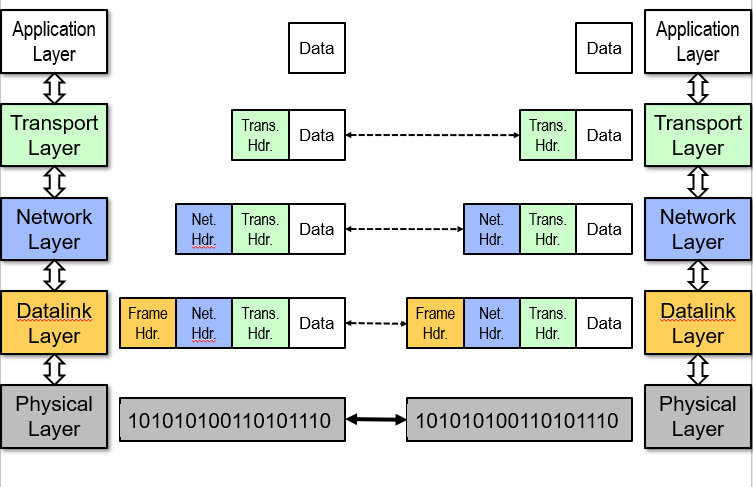

Layering

Introduce intermediate layers that provide set of abstractions.

-

Partition the system: Each layer solely relies on services from layer below, exports services to layer above

-

Interface between layers defines interaction: Hiding implementation details; Layers can change without disturbing other layers

OSI Model: 7 layers (application, presentation, session, transport, network, datalink, physical)

Internet Protocol (IP): Only five layers; The functionalities of the missing layers (i.e., Presentation and Session) are provided by the Application layer.

1 Physical Layer

Service: move information between two systems connected by a physical link

Interface: specifies how to send and receive bits

Protocol: coding scheme used to represent a bit, voltage levels, duration of a bit

2 Datalink Layer

Service: Enable end hosts to exchange frames (atomic messages) on the same physical line or wireless link; Possible other services:

-

Arbitrate access to common physical media

-

May provide reliable transmission, flow control

Interface: send frames to other end hosts; receive frames addressed to end host

- Each frame has a header containing a source and destination MAC address.

- MAC Address: uniquely identifies a network interface; 48 bit assigned by the manufacturer.

Protocols: addressing, Media Access Control (MAC) (e.g., CSMA/CD - Carrier Sense Multiple Access / Collision Detection)

- MAC Protocols (for broadcast channel): Hub / Switch LAN

- Channel partitioning protocols: 1/N bandwidth to each host (inefficient)

- Taking turns protocols: pass a token between active hosts (vulnerable)

- Random Access

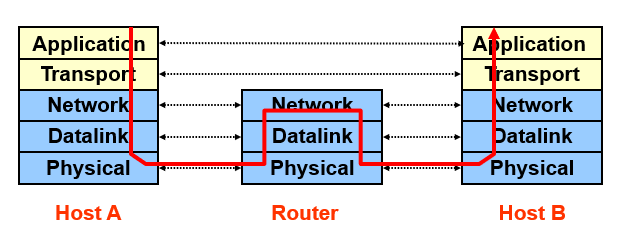

3 (Inter) Network Layer

Service: Deliver packets to specified network (IP) addresses across multiple datalink layer networks; Possible other services:

-

Packet scheduling/priority

- Buffer management

- IP Address: unique addr. assigned to each device by administrator or dynamically when device connected.

Interface: send packets to specified network address destination; receive packets destinated for end host

Protocols: define network addresses (globally unique); construct forwarding tables; packet forwarding

- Wide Area Network (WAN): connects multiple datalink layer networks using routers; different LANs can use different technologies

- Routers: Forward each packet on an incoming link to an outgoing link based on dst IP address; packets are buffered before forwarded. Forwarding table.

- IP Address vs MAC Address: location dependent, scalable.

4 Transport Layer

Service: Provide end-to-end communication between processes (In contrast, IP is end-to-end communication between hosts); Demultiplexing of communication between hosts (support multiple processes on the same hosts communicating simultaneously); Possible other services:

-

Reliability in the presence of errors

-

Timing properties

-

Rate adaption (flow-control, congestion control)

Interface: send message to specific process at given destination; local process receives messages sent to it

Protocol: port numbers, perhaps implement reliability, flow control, packetization of large messages, framing

- Port number: 16-bit number identifying endpoint of a transport connection (identifies a process, can be assigned by OS or requested by app)

- Transport Portocols: Datagram services(UDP), Reliable in-order delivery (TCP)

7 Application Layer

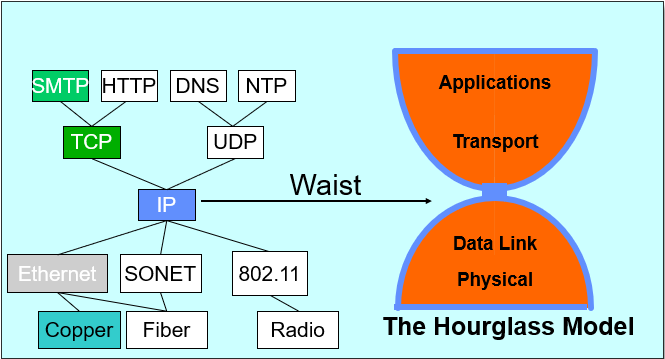

0 Hourglass Model

Single Internet-layer module (IP):

-

Allows arbitrary networks to interoperate: Any network technology that supports IP can exchange packets

-

Allows applications to function on all networks: Applications that can run on IP can use any network

-

Supports simultaneous innovations above and below IP; But changing IP itself, i.e., IPv6 is very complicated and slow

Performance Model

Single Packet Performance: Packet Delay

-

On each link: Propagation, Transmission

-

On each router: Processing, Queuing

Sustained Throughput: determined by bottlenect link

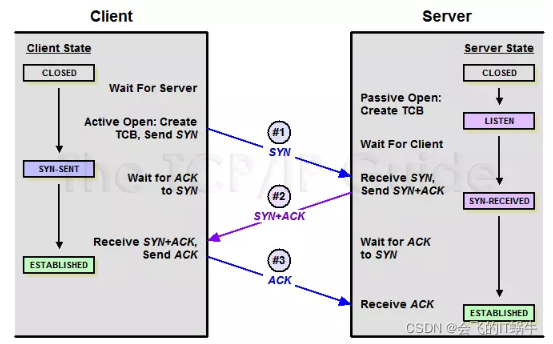

TCP: Transmission Control Protocol

UDP vs TCP

-

Reliable – guarantee delivery

-

Byte stream – in-order delivery

-

Connection-oriented – single socket per connection

-

Setup connection followed by data transfer

Solutions

- Ordered Message: Assign packet sequence numbers, through socket interface to sort upon arrival.

- Reliable Delivery: checksum and receive send acknowledge packet if received ungarbled; Resend if no acknowledgement, then deal with duplicates.

- How to ACK? Stop & wait protocol: If sender doesn’t receive ACK after a reasonable timeout, it retransmits frame.

- Window-based ACK: Send up to N packets without ack (Allows pipelining of packets); Ack says “received all packets up to sequence number X”.

- Congestion Avoiding: adjust window size.

Performance Implication

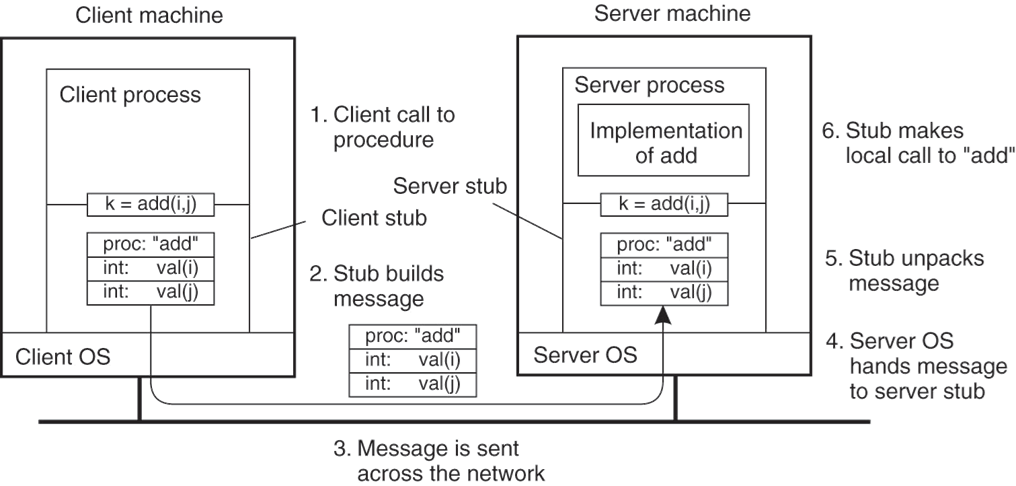

6.1 RPC

RPC: Remote Procedure Call

-

A type of client/server communication, attempts to make remote procedure calls look like local ones.

-

Goals: A nice abstraction than programming on the network, to make distribution transparent.

-

Challenges: possible failure, different running environment -> local rep. of data.

Basic Protocol

- Provides access to the exported methods of an object across a network or other I/O connection.

- A server registers an object, making it visible as a service with the name of the type of the object.

- After registration, exported methods of the object will be accessible remotely.

- A server may register multiple objects (services) of different types but it is an error to register multiple objects of the same type.

Stubs: Compiler generates from API stubs for a procedure on the client and server

-

Client stub

-

Marshals arguments into machine-independent format

-

Sends request to server

-

Waits for response

-

Unmarshals result and returns to caller

-

-

Server stub

-

Unmarshals arguments and builds stack frame

- Calls procedure

- Server stub marshals results and sends reply

-

Stubs and Marshaling

RPC stubs do the work of marshaling and unmarshaling -> understand the datatype?

- Write a description of function signature using interface definition language

- Passing value parameters:

RPC failure

Request lost, reply lost, server crash, client crash?

- Partial Failure: one cannot tell the difference of a machine failure and network failure. Make transparent to client?

- Strawman solution: Make remote behavior identical to local behavior.

- Real solution: break transparency

- Exactly once: impossible in practice

- At least once: for idempotent operations

- client keep trying until get a response

- At most once:

- server send previous reply and do not process replicate requests

- keep sliding window of valid (procecssed) RPC IDs.

- Zero or once: transactional semantics

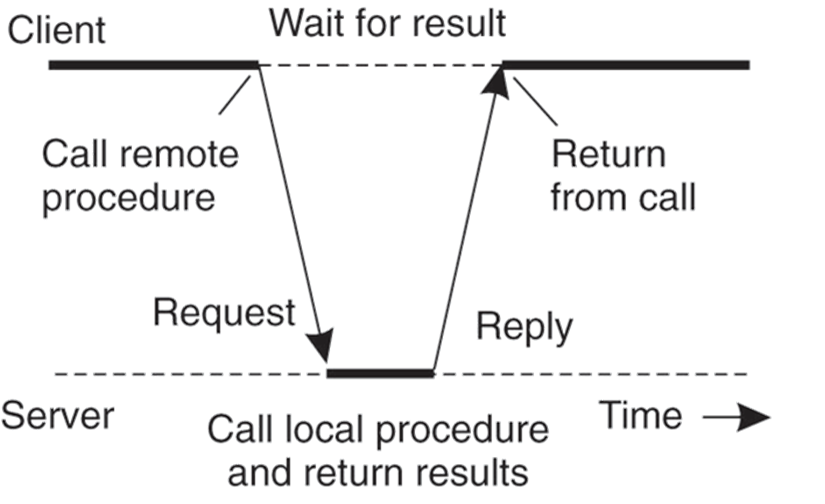

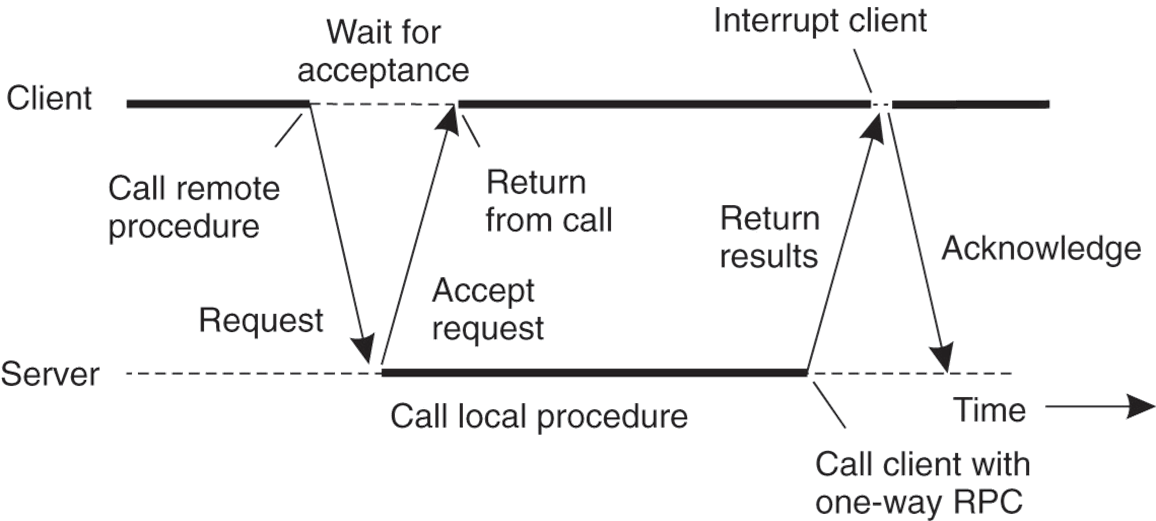

- Synchronous & Asynchronous RPC

6.2 Hard Drives

Disk, SSD

7 File System

File system: Layers of OS that transforms block interface of disks (or other) into files, directories, etc.

- Components: Disk Management, naming, protection, reliability/durability.

- Goals: maximize sequential performance, efficient random access to file, functionality

File System Interfaces

Durable data store => it’s all on disk

(Hard) Disks Performance: Maximize sequential access, minimize seeks

Open before Read/Write: Can perform protection checks and look up where the actual file resource are, in advance

Size is only determined as they are used: Can write (or read zeros) to expand the file; Start small and grow, need to make room

Organized into directories

Need to allocate / free blocks

Disk Management

File (Groups of sequentially arranged blocks), Directory (mapping of names to files)

Access disk as linear array of sectors (LBA, Logical Block Addressing)

- Every sector has integer address, from zero up to max number of sectors

- Controller translates from address to physical position

Functionality: (maintained somewhere in disk)

- Track free disk blocks

- Track block - file relation

- Track files in a directory

Components

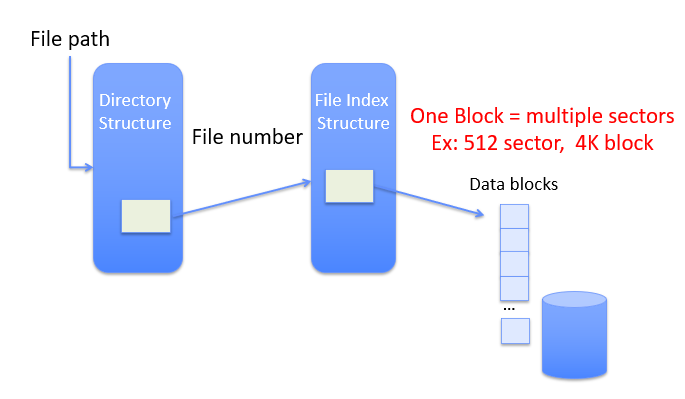

Name resolution: translate pathname into file number (as an index to locate blocks); create file descriptor; return a handle to user process (mapped to descriptor and blocks)

Directory

Basically a hierarchical structure. Each directory entry is a collection of files or directories (a link to another entries)

Each has a name and attributes.

Links (hard links) make it a DAG, not just a tree.

- Soft links (aliases) are another name for an entry

File

Named permanent storage, contains data (blocks on disk somewhere), metadata (attributes, including owner, size, last opened, access rights, …)

In-memory File System Structure

-

Open system calls:

-

Resolves file name, finds file control block (inode)

-

Makes entries in per-process and system-wide tables

-

Returns index (called “file handle”) in open-file table

-

-

Read/write system calls:

-

Use file handle to locate inode

-

Perform appropriate reads or writes

-

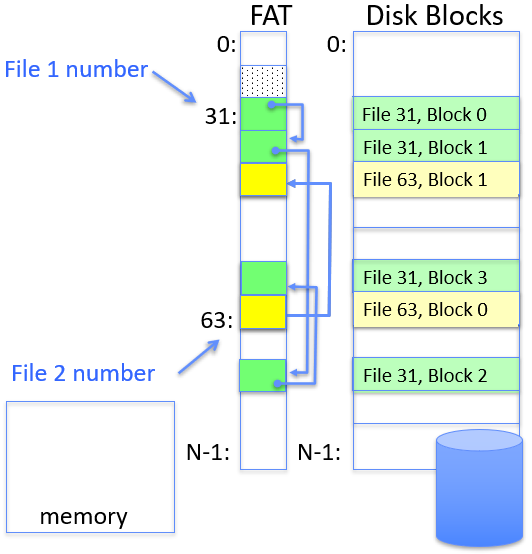

FAT (File Allocation Table)

Disk storage is a collection of blocks (offset o = <B,x>)

Each FAT item: corresponds to a block, pointing to the next block of the file (linked list structure); file number is exactly the index of block list root.

- Allocating a new block: scan to find one marked free

- mark all entries free when formating a disk

- No access rights design, no header in file blocks

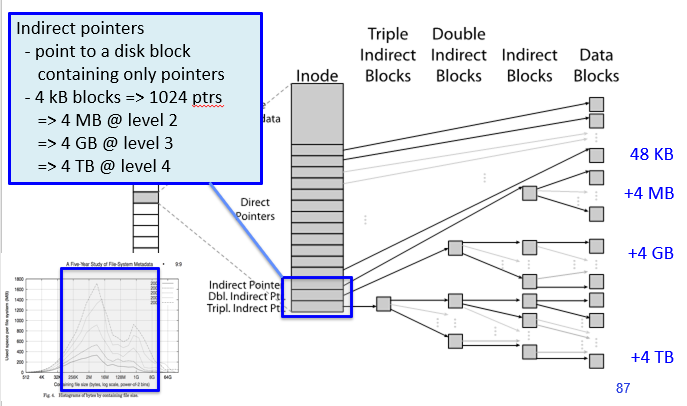

UNIX BSD 4.1

- File Metadata: Arributes including user, group, access control bits,

- Data storage: 12 pointers direct to data blocks (for small files); 3 levels of indirect pointers

UNIX BSD 4.2 (FFS)

Uses bitmap allocation in place of freelist; Attempt to allocate files contiguously

- To expand a file, try successive blocks in bitmap and choose new range of blocks

- Store files from same directory near to each other

10% reserved disk space

Skip-sector positioning

- Purpose: Avoid Rotational Delay

- Skip Sector positioning (interleaving): Place the blocks from one file on every other block of a track: give time for processing to overlap rotation

- Read ahead: read next block right after first, even if application hasn’t asked for it yet

Inode storage: a fixed number of inodes are created at formatting time (inumber)

- Often, inode for file stored in same cylinder group as parent directory (fast ls)

File Access Pattern & Usage Pattern

Directories and links

-

link File1 File2: link existing filefile1to a directory. Forms a DAG - Hard link: Sets another directory entry to contain the file number for the file; Creates another name (path) for the file (same inode)

- Soft link (or Symbolic Link or Shortcut): Directory entry contains the path and name of the file; Map one name to another name (different inode)

Storage Reliability

Availability: the probability that the system can accept and process requests

- Often measured in “nines” of probability. So, a 99.9% probability is considered “3-nines of availability”

Durability: the ability of a system to recover data despite faults

-

This idea is fault tolerance applied to data

-

Doesn’t necessarily imply availability

Reliability: the ability of a system or component to perform its required functions under stated conditions for a specified period of time

-

Usually stronger than simply availability: means that the system is not only “up”, but also working correctly

-

Includes availability, security, fault tolerance/durability

-

Must make sure data survives system crashes, disk crashes, other problems

-

Threats: Interrupted Operation; Loss of stored data

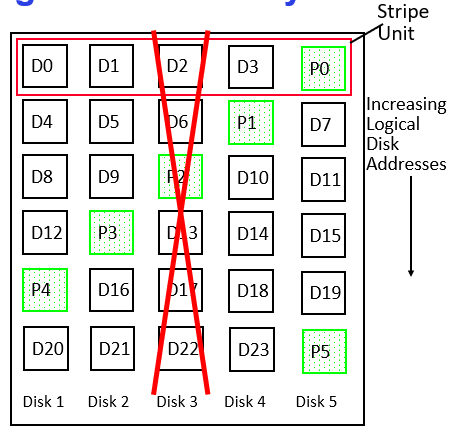

RAID: Redundant Arrays of Inexpensive Disks

Data stored on multiple disks (redundancy), either by software or hardware

- RAID 1: disk mirroring/shadowing

- Each disk is fully duplicated on its shadow

- write bandwidth is sacrificed, while read may be optimized

- Recovery: upon failure, replace disk and copy data to the new disk.

- RAID 5+: High I/O Rate Parity, each row XORs to zero.

- Could spread information widely across internet for durability

File System Reliability (against system failure)

Durability: Data previously stored can be retrieved (maybe after some recovery step), regardless of failure

Approach 1: Careful Ordering

Sequence operations in a specific order: Careful design to allow sequence to be interrupted safely

Post-crash recovery: Read data structures to see if there were any operations in progress, clean up/finish as needed

Approach taken by

-

FAT and FFS (fsck) to protect filesystem structure/metadata

-

Many app-level recovery schemes (e.g., Word, emacs autosaves)

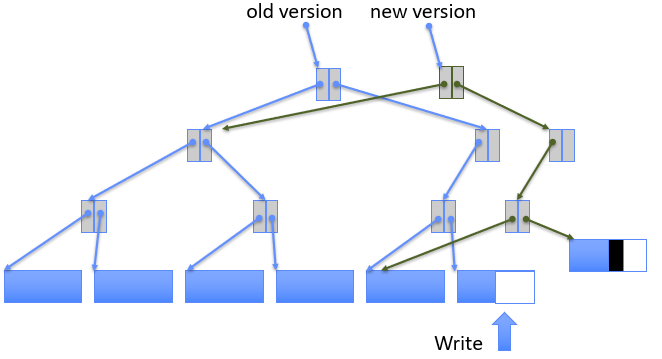

Approach 2: Copy on Write (COW) File Layout

To update file system, write a new version of the file system containing the update. Never update in place, reuse existing unchanged disk blocks

Seems expensive, but (1)Updates can be batched; (2)Almost all disk writes can occur in parallel; (3)If file represented as a tree of blocks, just need to update the leading fringe.

Approach taken in network file server appliances

-

NetApp’s Write Anywhere File Layout (WAFL)

-

ZFS (Sun/Oracle) and OpenZFS

More General Reliability Solutions

Use Transactions for atomic updates: Ensure that multiple related updates are performed atomically

Transactions: An atomic sequence of actions (reads/writes) on a storage system (or database), that takes it from one consistent state to another

- Structure:

- Begin - get transaction id

- Do a bunch of updates (rollback upon failure or conflicts)

- Commit transaction

- ACID properties

Logging

All changes are treated as transactions; A transaction is committed once it is written to the log

-

Data forced to disk for reliability

-

Process can be accelerated with NVRAM

Although File system may not be updated immediately, data preserved in the log.

Journaling File System: Applies updates to system metadata using transactions (using logs, etc.)

-

Updates to non-directory files (i.e., user stuff) can be done in place (without logs), full logging optional

-

Ex: NTFS, Apple HFS+, Linux XFS, JFS, ext3, ext4

Full Logging File System: All updates to disk are done in transactions

Journaling File Systems

Instead of modifying data structures on disk directly, write changes to a journal/log

-

Intention list: set of changes we intend to make, append-only

-

Single commit record commits transaction

Once changes are in the log, it is safe to apply changes to data structures on disk

-

Recovery can read log to see what changes were intended

-

Can take our time making the changes, as long as new requests consult the log first

Once changes are applied, safe to remove log

LFS: Log Structured File Systems

8 Caching

Direct-mapped, fully-associative, set-associative (Tag-Index)

Replace policy: Random, LRU

Write policy: write through v.s. write back

TLB: Caching memory translation

Translation look-aside buffer: locality in accesses$\to$locality in translations

- A hardware cache containing PTEs (for page table).

- TLB entry Organization: a PTE, valid bit, tag, LRU info, …

- Miss handling: Page Table Walk, access PTE in memory, and then call for that page.

TLB Context switching: flush all & add pid to identify

Demand Paging

When page fault occurs, the pages needs to be paged in. Invoke OS page fault handle to move data from storage into memory (extremely slow)

Page Replacement policies: FIFO, random, LRU

Approximated LRU: Second Chance, Clock algorithm

9 Blockchains

Target: decentralized, history-trackable, unchangeable once confirmed

(Local) Data Structure

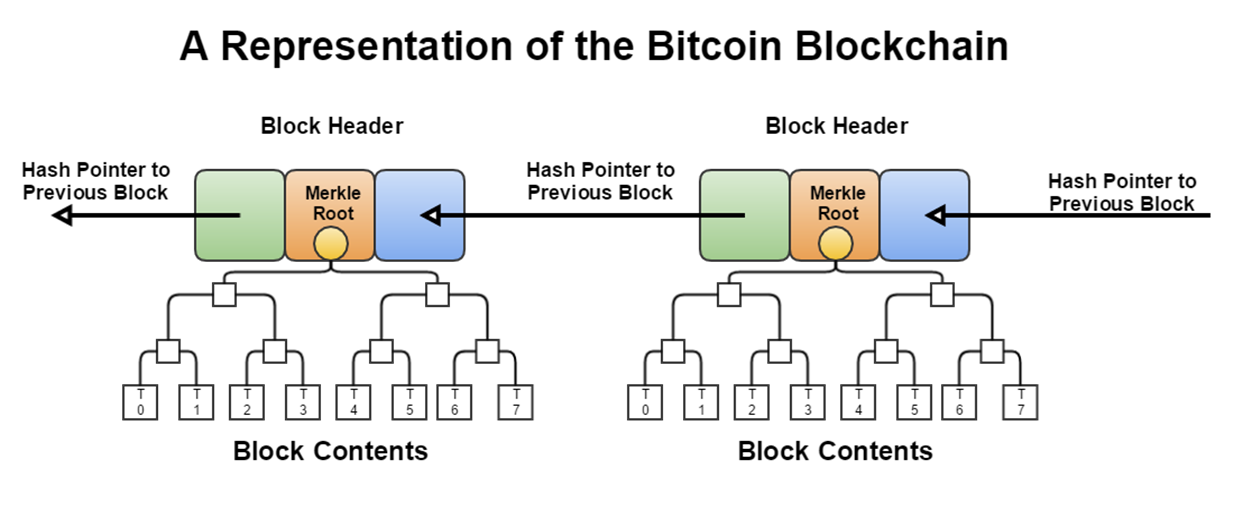

Hash pointer: a pointer to where some info is stored; a (cryptographic) hash of the info.

- With a hash pointer, we can (1)ask to get the info back, and (2)verify that it hasn’t changed

Merkle Tree: Binary tree of hash pointer; proof of membership or non-membership

Block: time, nonce, previous hash, body

Distributed Blcokchain: Bitcoin P2P network

No leader node (decentralized), New nodes can join at any time, Forget non-responding nodes after 3 hr

Consensus: (Liveness) Can we eventually reach concensus? (Latency) How long before a transaction becomes consensus? (Correctness) What if two contradicting transactions are proposed in the network?(Throughput) How many transactions can be processed per minute?

A simplified algorithm: (1) New transactions are broadcast to all nodes (2) Each node collects new transactions into a block (3) In each round a random/selected node gets to broadcast its block (4) Other nodes accept the block only if all transactions in it are valid (unspent, valid signatures) (5)Nodes express their acceptance of the block by including its hash in the next block they create

To approximate selecting a random node: select nodes in proportion to a resource that no one can monopolize (we hope)

-

E.g. In proportion to computing power: proof-of-work (PoW)

-

E.g. In proportion to ownership: proof-of-stake (PoS)

-

Hash puzzles: to create a block, we should find nonce st. H(header nonce) is very small - PoW: Brutal search all possible nonce, and find the nonce satisfying the threshold. (Mining)

- Good properties: difficult to compute, perameterizable cost, trivial to verify

Creator of block gets to

-

include special coin-creation transaction in the block, i.e., “coinbase” reward

-

Receive all transaction fees (tips)

Longest Chain Rule: (The Nakamoto Protocol) When facing different versions of the chain, follow the longest one.

10 Distributed Syncronization(I)

Distributed system: A collection of independent computers that appears to its users as a single coherent system.

Characteristics:

- Present a single-system image

- Easily expandable: adding new servers is hedden from users

- Continuous availability: failuers in one component can be covered by other components

- Supported by middleware

Problems:

- Worse availability

- Worse reliablity

- Worse security

Time Synchronization

Perfect network: with propagation delay exactly $d$, then set time to $T+d$ upon receiving time $T$ from the sender.

Synchronous network: with propagation error at most $d$, then set time to $T+d/2$ so the synchronization error is at most $d/2$.

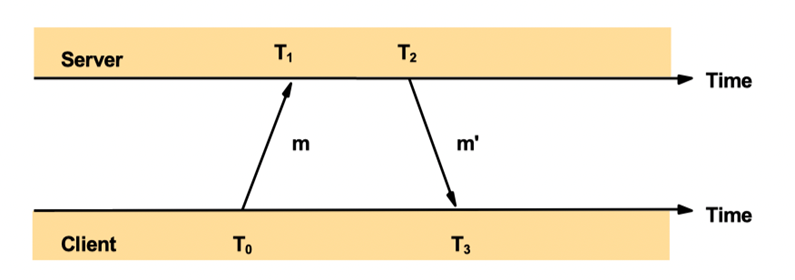

Cristian’s Time Sync: process $p$ requests time in message $m_R$ to the time server S, receives time value $T$ from message $m_T$ after time RTT. Then $p$ sets its clock to T+RTT/2. (RTT: round trip time)

- Accuracy: RTT/2 - min, min = estimated minimum one-way delay

- Work well when RTT « desired accuracy; RTT increases if S is visited by many people.

Berkeley Alogrithm: time master uses Cristian’s algorithm: (1) send its own time to others; (2) get time difference from others, to get time from many clients; sends time adjustment (average difference) back to all clients.

Network Time Protocol (NTP)

Goal: A time service for the Internet–synchronizes clients to UTC reliably from multiple, scalable, authenticated time sources

Uses a hierarcy of time servers

-

Class 1 servers have highly-accurate clocks

-

Class 2 servers get time from only Class 1 and Class 2 servers

-

Class 3 Servers get time from any server

Protocol: all messages use UDP

T0,T1,T2,T3 are recorded and finally received by the client; client adjust time to $T_3 + ((T_1-T_0) + (T_2 - T_3))/2$ upon receiving m’ at time T3.

Logical Clocks

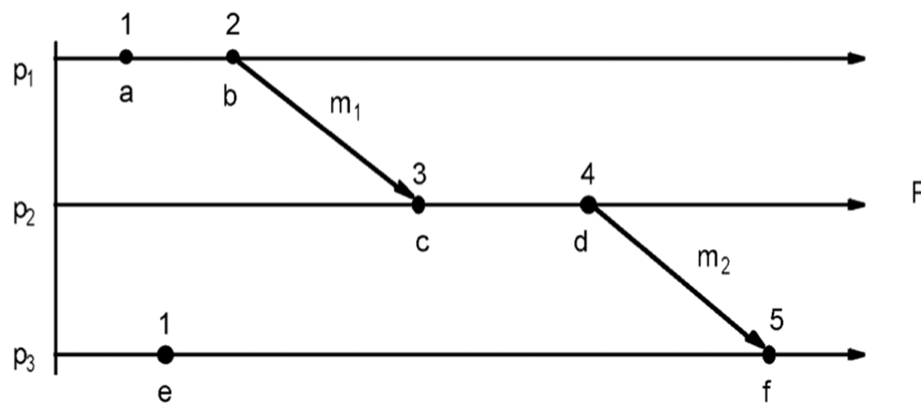

Each process consists of a sequence of events, with a local event order.

Communication is done via sending and receiving messages, each is an event.

| Ordering: $a\to b$ of a may causally affect b; $a | b$ if a and b are concurrent (not causally affect each other) |

Logical Time (Lamport Time): Capture just the happens-before relationship between events

Two scenarios where “happens-before” relation can be directly observed:

-

Two events occurred at same process pi (i = 1, 2, … N): then they occurred in the order observed by pi .

- When message m is sent between two processes: send(m) happens before receive(m).

- Transitive property

Clock Rules: each process $p_i$ has a logical clock $L_i$ which can be used to apply logical timestamps to events

- $L_i$ is incremented by 1 before each event at process $p_i$.

2a. When process $p_i$ sends message $m$, it piggybacks $t = L_i$

2b. When $p_j$ receives $(m, t)$ it sets $L_j := \max(L_j , t)$ and applies Rule 1 before timestamping the event receive(m)

| Properties: (1) $e\to e’$ implies L(e)<L(e’) (2) L(e)=L(e’) implies e | e’ |

Total order Lamport Clock: break tie using pID: $L(e) = M\times L_i(e) + i$ for process i and M = #processes.

Vector Clock

Initially, all vectors [0,0,…,0]; For event on process i, increment own $c_i$.

When process j receives message with vector $[d_1, d_2, …, d_n]$:

-

Set each local entry k to $\max(c_k, d_k)$

-

Increment value of $c_j$

Properties: (1) $e\to e’$ iff $V(e) < V(e’)$ for every component (2) e || e’ iff neither $V(e) \le V(c)$ nor $V(c) \le V(e)$.

11 Distributed Syncronization

Totally Ordered Multicast

A multicast operation by which all messages are delivered in the same order to each receiver. Algorithm:

-

Message to be sent is timestamped with sender’s logical time

-

Message is multicast (including to the sender itself)

-

When message is received:

3a) It is put into local queue

3b) Ordered according to timestamp (priority queue)

3c) Receiver multicasts acknowledgement

Message is delivered to applications only when

-

The message is at head of queue

-

The message has been acknowledged by all involved processes

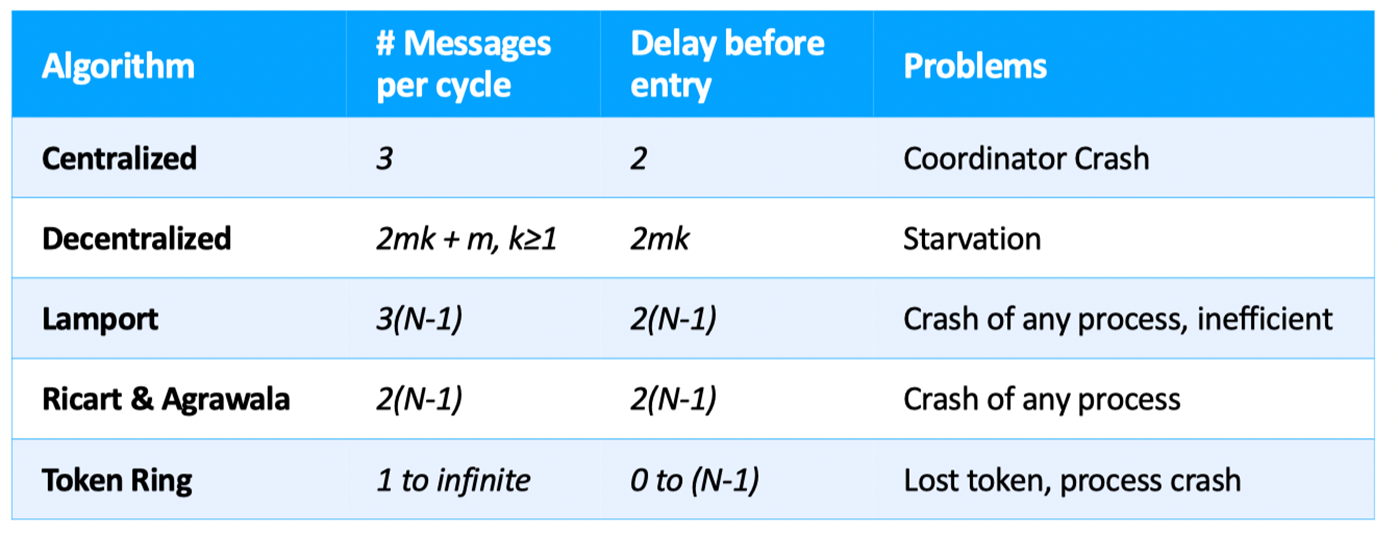

Distributed Mutual Exclusion

Requirements: safety/correctness, fairness, no shared memory, tolerate OoO messages, efficiency

Centralized

Elect a leader and it decide to which client the mutex is assigned (through messages) Leader election: bully algorithm

- A server P notices the leader ahs failed, and send an ELECTION messages to all others

- If no one responds, P wins the election and becomes coordinator.

- If one of the higher-ups answers, it takes over. P’s job is done.

Fully Decentralized Voting

Send a request to all coordinators, and is granted only if get a majority vote from M>n/2 coordinators.

Lamport Mutual Exclusion

Every process holds a queue of pending requests;

- When a node wants to enter C.S., multicast time-stamped request to all others (including itself) and wait for reply from all others

- After receiving a request,add the request in its own request queue (ordered by timestamps) and reply with the timestamp.

- If a node’s own request is at the head of its queue and all replies have been received, enter C.S..

- Upon exiting C.S., remove its request from the queue and multicast a release message to every process.

- After receiving release message, remove the corresponding request from its own request queue, and check 3.

Ricart & Agrawala

When node i wants to enter CS, it multicasts timestamped request to all other nodes. These other nodes reply (eventually):

- If it’s uninterested, simply reply OK; if it’s currently using, simply reply nothing.

- If it wants to access the resource, compare the timestamp of imcoming message and its previously sent message. (reply after using v.s. immediately reply)

When i receives n-1 (all other) replies, then it can enter C.S.

Token Ring

Organize the processes involved into a logical ring. One token at any time $\to$ passed from node to node along ring

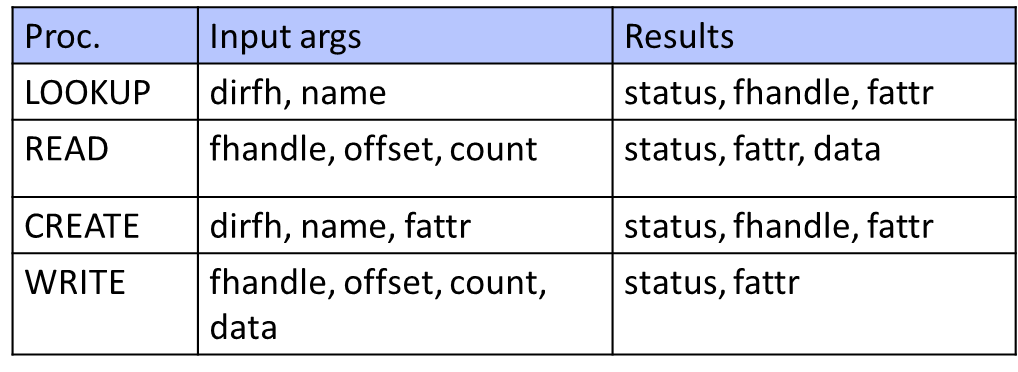

12 Distributed File System

Access to data stored at servers using file system interfaces Challenges: heterogeneity, scale, security, failures, concurrency, distance & latency Goals: scale, user-centric workloads

Key components: client side, communication layer, server side, virtual FS(VFS)

Naive approach: RPC

Client use RPC to forward FS ops to the server; Server serializes all accesses, performs them, and sends back result.

Distributed Cache

Data may be written by other machines (cache stateness…) (1) Broadcast invalidation: simple, extra communication, not scalable (2) Check on use: simple, but slow and not scalable (3) Callback: Clients register with server that they have a copy of file, server tells them: “Invalidate!” if the file changes (AFS) (4) Leases: Granting exclusive/shared control of the cached objects for a limited amount of time

In NFS v2:

Cache both clean and dirty file data and file attributes File attributes (metadata) in the client cache expire after 60 seconds (file data doesn’t expire) File data is checked against the modified-time in file attributes (which could be a cached copy)

- Changes made on one machine can take up to 60 seconds to be reflected on another machine

Dirty data are buffered on the client machine until file close or up to 30 seconds

- If the machine crashes before then, the changes are lost

Failures

Server crashes: data in memory are lost; Lost messages Client crashes: may lose data in the client cache;

NFS’s failure handling:

-

operations are idempetent: unique IDs for failes & directories

-

write-through caching: close() does not return until bytes are safely stored.

-

simple, portable, but with weak consistency semantics

Andrew File System (AFS)

Large number of clients and servers, minimize work per client operation. Assumptions: (1) disks; (2) W/W or W/R sharing are rare; (3) Untrusted clients Structure: Cell - administrative groups; Volumes -

-

More aggressive caching (AFS caches on disk in addition to just in memory)

- Prefetching (on open, AFS gets entire file from server, making later ops local & fast).

- Improves scalability, particularly if client is going to read whole file anyway eventually.

Callbacks: When server crashes, reconstruct callback information from client; When client crashes, revalidate any cached content it uses since it may have missed callback

RPC Procedures:

(1) Fetch: return status and optionally data of a file or directory, and place a callback on it

(2) RemoveCallBack: specify a file that the client has flushed from the local machine

(3) BreakCallBack: from server to client, revoke the callback on a file or directory

(4) Store: store the status and optionally data of a file

AFS Consistency

A file write is visible to processes on the same box immediately, but not visible to processes on other machines until the file is closed; When a file is closed, changes are visible to new opens, but are not visible to “old” opens; Last writer (i.e. the last close()) wins

Implementation: Dirty data are buffered at the client machine until file close, then flushed back to server, which leads the server to send “break callback” to other clients.

- lower server load, but may be slower;

- both NFS and AFS: certral server is bottleneck; a single point of failure; costly to make fast and reliable

Naming

NFS: per-client linkage

AFS: global name space, namespace is organized into volumes

- /afs/cs.wisc.edu/vol1/…; /afs/cs.stanford.edu/vol1/…

- Each file is identified as fid = <vol_id, vnode #, unique identifier>

- All AFS servers keep a copy of “volume location database”, which is a table of vol_id $\to$ server_ip mappings (So location-transparent: client needn’t remount when a volume is moved)

13 Distributed Transactions

CAP Theorem: Consistency, Availability and Partition-resilience cannot be all achieved. CP: Paxos, consensus algos, state mechine AP: Coda, Github CA: consistent replication with service from any replica

Fischer-Lynch-Paterson (FLP): no consensus can be guaranteed in an asynchronous communication system in the presence of any failures. Correct consensus: Termination, Agrrement, Integrity

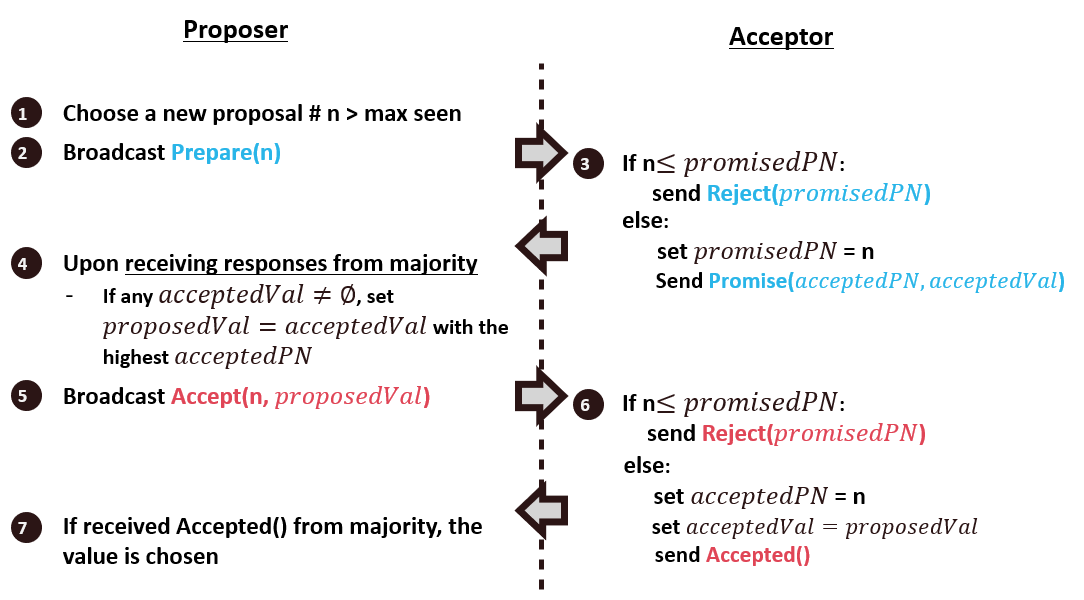

Paxos Algorithm

Key idea: if a value is chosen by the majority, we must let the value to remain unchanged.

Prepare phase: proposer broadcast Prepare(n) and wait for acceptsand collect responses

-

To see if there is a chosen value already

-

To invalidate older proposals that have not completed yet

Accept Phase: Broadcast the accept message with a proposed value, and value is chosen if received majority votes

2-Phase Commit

When we want to commit a Tx on multiple nodes:

Each transaction commit is led by a coordinator (C, or transaction manager TM) Other participants in 2PC are called Resource Managers or RMs (P)

Phase 1: C is notified, and it requests each P to prepare; P validate the request, prepare and vote (whether Tx is “prepared” at P)

Phase 2: C commits if all P vote to commit, C writes a commit record; else abort. Then C notifies the result to each P

Consistency Models

What is consistency? Read-only consistency: easy, just make multiple copies Read-write: require write replication

From a programmer’s view: Do my reads always get latest values? Does writes/updates obey the real time order? Will I read my own updates?

These surprises are tolerated for performance and availability.

- Strict Consistency: act just like a sigle machine

- Linearizability: if there exists a total order of all orperations such that for non-overlapping operations, the real time is obeyed and always read latest writes.

-

Sequential Consistency: all nodes see operations in one (the same) sequential order, and operations of each process appear in-order in this sequence.

- Causal Consistency: all nodes see potentially causally related writes in same order, but concurrent writes may be seen in different order.

- Eventual Consistency: consistency will be achieved eventually, and temporary inconsistency can be tolerated (by human-involved systems)